Remembering Hurricane Camille

Thursday, January 9th, 2020

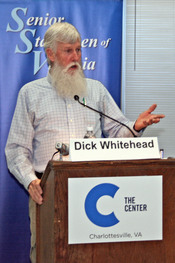

Dick Whitehead

Dick Whitehead, PG, is the resident project representative with Wiley|Wilson, a 100% Employee-Owned engineering firm in Lynchburg. His father, Bill Whitehead, was the Nelson County sheriff during Hurricane Camille. Dick was a teenager during Camille and helped his father look for the bodies of the missing.

Hurricane Camille arrived in Virginia on the night of August 19, 1969, one of only three category five storms ever to make landfall in the United States since record-keeping began. One of the worst natural disasters in Virginia’s history, the storm produced what meteorologists at the time guessed might be the most rainfall “theoretically possible.” As it swept through Virginia overnight, it seemed to catch authorities by surprise. Communication networks were not in place or were knocked out, leaving floods and landslides to trap residents as they slept. Hurricane Camille cost Virginia 113 lives lost and $116 million in damages. It also served as a lesson that inland flooding could be as great a danger as coastal flooding during a hurricane.

The program was moderated by SSV Board Member Madison Cummings, and the podcast follows.

Program Summary

Working with two of his colleges, Jeff Halverson meteorologist and Ann Witt geohazard geologist, Dick Whithead, a geologist, has studied the local conditions that led to the disaster. Twenty-seven inches of rain which did not drift due to the vertical storms on top of the rock formations and topography of the terrain led to landslides and flooding. This storm occurred at night in total darkness as power was out in the whole area.

By ten o’clock on the night of August 19, Camille stretched from West Virginia all the way to Fredericksburg, Virginia, and areas to the north and east of the center of the storm were experiencing very heavy rainfall. The rain landed on the eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains, rapidly swelling creeks and exacerbating the effects of the storm. Overnight, rainfall accumulations were measured at about ten inches between Charlottesville and Lynchburg, with Nelson County receiving the brunt of the storm with at least twenty-seven inches of rainfall. So much rain fell in such a short time in Nelson County that, according to the National Weather Service at the time, it was “the probable maximum rainfall which meteorologists compute to be theoretically possible.”

As the water flowed down the mountains, first the large boulders fell out of the suspension, then came trees and debris followed by the sandy sediment. In photos one can see the massive debris field left by these slides. In total 5,600 landslides have been documented during the event and one small stream recorded water 23 feet deep. Studies have shown that 65 percent of the deaths associated with the storm were caused by landslides and the remaining 35 percent of victims drowned.

A new technology, Lidar-Data Laser, which can see through the trees to the original land is providing more details about the land to help study earth’s surface to explain why landslides occur where they do. It has been found that slopes of greater than 25 degrees and six to ten inches of rain in 24 hours are indicators of landslide potential.

During the question and answer period one woman recounted being with her children in her home with a tin roof during the storm and the terror she felt. When asked Dick replied, “Yes, it could happen again.”